Euphanerops

(24 kb) Baptized Euphanerops longaevus, this animal’s unique features fascinated paleontologists.

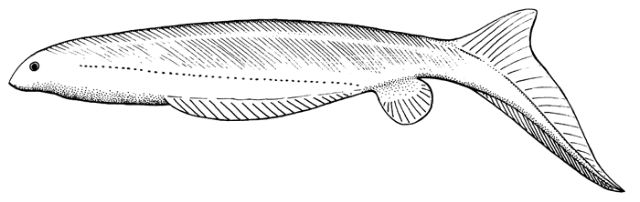

(24 kb) Baptized Euphanerops longaevus, this animal’s unique features fascinated paleontologists.The absence of paired fins and the somewhat poor preservation of the head made it difficult to distinguish top from the bottom. This is why Woodward’s first illustrations show Euphanerops upside-down, with an epicercal tail and dorsal fin instead of a hypocercal tail and anal fin. This inverted representation suggests that Mr. Woodward’s interpretation was influenced by the paleontological beliefs of his day, which held that any hypothetical ancestor of the gnathostomes must have had an epicercal tail.

More than a century later, the species was better described and presented right side up. We now know that its tail was strangely similar to those of the Silurian anaspids, and that its gill apparatus was exceptionally long, with thirty gill pairs from head to anus. This surprising discovery means that the branchial basket stretched almost the entire length of its body, requiring a significant rearrangement of its other inner organs. This extreme specialization, which has never been found in any other vertebrate group, was likely an adaptation to life in oxygen-poor waters, like those of the Miguasha estuary.

(64 kb)In 1991, and for several years after, researchers thought that they had unveiled another new anaspid species at Miguasha. Baptized Legendrelepis parenti, this fish differed from Euphanerops longaevus by the greater separation between its anal fin and tail, and the possible presence of a very small dorsal fin. These details turned out to be artifacts of preservation, and both species are now thought to be one and the same.

(64 kb)In 1991, and for several years after, researchers thought that they had unveiled another new anaspid species at Miguasha. Baptized Legendrelepis parenti, this fish differed from Euphanerops longaevus by the greater separation between its anal fin and tail, and the possible presence of a very small dorsal fin. These details turned out to be artifacts of preservation, and both species are now thought to be one and the same.

(24 kb)Like the agnathans, Euphanerops had a cartilaginous internal skeleton. A recent microscope study of various endoskeletal features revealed that the cartilaginous structures had begun to calcify in mature specimens. The manner in which the cartilage was undergoing ossification is quite unusual, and is comparable to the cartilage of today’s lampreys that can be partially calcified by artificial means in the laboratory. Could this represent an evolutionary attempt towards endoskeleton calcification, a trend that was developing concurrently in the gnathostome group?

(24 kb)Like the agnathans, Euphanerops had a cartilaginous internal skeleton. A recent microscope study of various endoskeletal features revealed that the cartilaginous structures had begun to calcify in mature specimens. The manner in which the cartilage was undergoing ossification is quite unusual, and is comparable to the cartilage of today’s lampreys that can be partially calcified by artificial means in the laboratory. Could this represent an evolutionary attempt towards endoskeleton calcification, a trend that was developing concurrently in the gnathostome group?Ongoing studies of many new specimens of the curious Euphanerops “anaspid” are revealing unique anatomical details, some of which move it closer to lampreys, and others that are more reminiscent of the first vertebrates to have evolved in Early Cambrian time. This animal undoubtedly has more surprises in store for us!

Site map | Feedback | Links | Sources | Credits

Euphanerops

<< Endeiolepis | Osteostracans >>

Title: Euphanerops longaevus

Author: Illustration FROM François Miville-Deschênes

Sources: Parc national de Miguasha

Year: 1999

Description:

A specimen of Euphanerops with the impression of the long branchial basket visible on the ventral side of the animal. Also evident is the strongly downward-pointing axis of the tail (caudal fin).

Title: Euphanerops longaevus

Author: Parc national de Miguasha

Sources: Parc national de Miguasha

Year: 2003

Description:

A specimen of Euphanerops with the impression of the long branchial basket visible on the ventral side of the animal. Also evident is the strongly downward-pointing axis of the tail (caudal fin).