The geology craze of the 19th century

(44 kb) In England, the industrial revolution was driving the quest for coal, an indispensable source of energy. It was from this need to explore and understand the subsurface that the sciences of stratigraphy, the study of sedimentary layers, and paleontology, which characterized layers based on fossil content, were born. And so, at long last, the geological time scale was beginning to take shape.

(44 kb) In England, the industrial revolution was driving the quest for coal, an indispensable source of energy. It was from this need to explore and understand the subsurface that the sciences of stratigraphy, the study of sedimentary layers, and paleontology, which characterized layers based on fossil content, were born. And so, at long last, the geological time scale was beginning to take shape.Spurred on by the spirit of adventure, the first geologists set out across the land equipped with maps showing rock formations and their fossil fuel resources. The geology craze spread to their colonies and to other nations undergoing industrialization. In 1842, Canada established the Geological Survey of Canada (GSC) with the goal of discovering energy resources that would ensure the young nation’s prosperity.

The following year, the GSC began its first and very ambitious geological mapping program: the complete geological coverage of Canada. It should be pointed out that in the middle of the 19th century, Canada’s territory was in its early stage, comprising only southern Ontario and southern and eastern Quebec – the newly united Upper and Lower Canada.

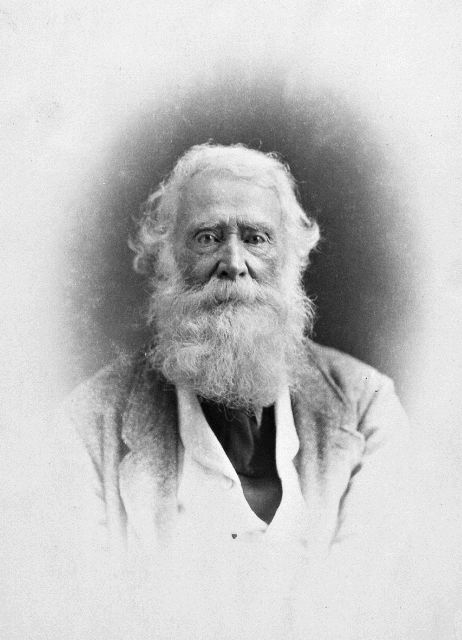

(76 kb)As part of this initiative, William E. Logan, the GSC’s first president (a post he would hold for 27 years), travelled to the Gaspé region in 1843 to begin mapping. His field work eventually sent him to all the corners of the fledgling nation, and Logan finally presented the first geological map of Canada at the world exhibit in Paris in 1855.

(76 kb)As part of this initiative, William E. Logan, the GSC’s first president (a post he would hold for 27 years), travelled to the Gaspé region in 1843 to begin mapping. His field work eventually sent him to all the corners of the fledgling nation, and Logan finally presented the first geological map of Canada at the world exhibit in Paris in 1855.Another major turning point in the 19th century occurred in 1859 when the British naturalist, Charles Darwin, launched his pivotal book The Origin of Species. In it, he published ideas that were already popular in scholarly circles: that living species are able to transform, adapting themselves to their environment, and thus give rise to new species. Darwin’s novel contribution, however, was to present supporting evidence and to propose a mechanism for evolution, which he called natural selection. In those days, the ideas shocked many people of a puritanical and religious mindset.

Around the middle of the 19th century, advances in the field of geology were supporting the idea of a very old Earth, and the field of biology was providing evidence that living creatures evolved over millions of years. Paleontology arose as a product of both disciplines, a necessary step for dealing with fossilized specimens of the many mysterious organisms that long ago disappeared. It was in this revolutionary scientific context that Miguasha was first discovered in 1842, and in a fortuitous coincidence, Darwin completed his manuscript on the theory of evolution that very same year!

Site map | Feedback | Links | Sources | Credits

The geology craze of the 19th century

<< Miguasha fossils around the world | The first discoveries >>

Title: Sir William Edmond Logan

Author: William Notman

Sources: Notman photographic archives, McCord Museum

Year: 1871

Description:

Sir William Edmond Logan (1798-1875) was in charge of setting up the Geological Survey of Canada in 1842, and the following year he began roaming the Gaspé Peninsula to conduct the first geological mapping survey along its coasts. Geology and paleontology were fairly new and unknown sciences at the time, and the famous geologist was consequently described by some as an idiot who hammered the ground with his pick!

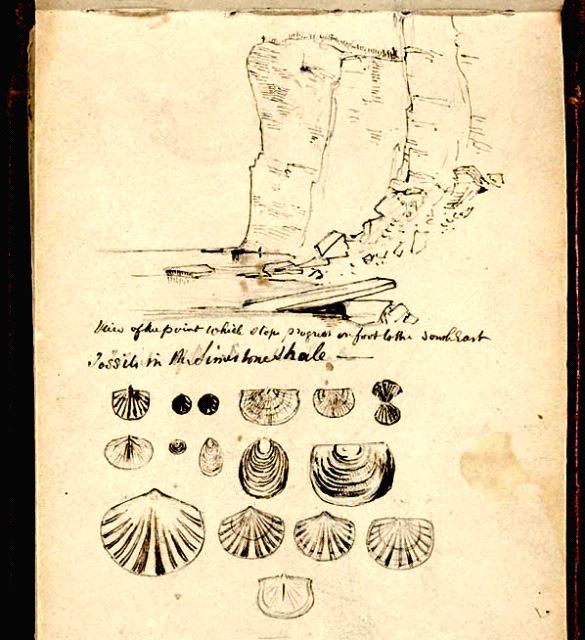

Title: Logan’s notebook, 1843

Author: Sir William Logan

Sources: Canada Archives

Year: 1843

Description:

Logan had the good habit of adorning his field notes with drawings of the landscape and fossils he came across. Taken from a page of his field book of 1843, this drawing shows the Lower Devonian cliff at Cap Bon Ami, which is now part of the Forillon National Park of Canada on the seaside edge of the Gaspé Peninsula.