Actinopterygians

Do you eat actinopterygians? If you enjoy salmon, cod, tuna, herring or trout... then your answer is yes.

(24 kb) The term actinopterygian has Greek roots from pterugion (fins) and aktinos (rays). Behind this word lurk the ray-finned fish, a definition that includes all jawed actual fish except sharks, rays and chimaeras, as well as some rare sarcopterygian fish. At present, actinopterygians include more than 29,000 species, which accounts for more than 50% of all vertebrates! They are found in all aquatic habitats, from small freshwater creeks to great ocean depths, and from the smallest ponds to the greatest estuaries.

(24 kb) The term actinopterygian has Greek roots from pterugion (fins) and aktinos (rays). Behind this word lurk the ray-finned fish, a definition that includes all jawed actual fish except sharks, rays and chimaeras, as well as some rare sarcopterygian fish. At present, actinopterygians include more than 29,000 species, which accounts for more than 50% of all vertebrates! They are found in all aquatic habitats, from small freshwater creeks to great ocean depths, and from the smallest ponds to the greatest estuaries.

Actinopterygians have pectoral fins made from a membrane upheld by several semi-rigid rays, called lepidotrichia, that are all attached to a single peduncle. This characteristic distinguishes them from placoderms, which have very large, limb-like basal pectoral fins, and acanthodians, equipped with immobile fins made from a single spine supporting a small membranous veil.

The fins of actinopterygians are among the most efficient in the aquatic world, not only because they allow for powerful swimming, but also (perhaps mainly) because they confer stability and manoeuvrability. The evolutionary success of this group is largely due to this morphological innovation.

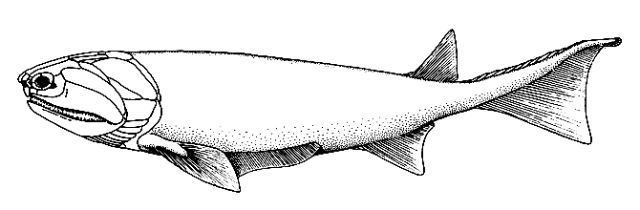

The first actinopterygians go back to the end of the Silurian or the beginning of the Devonian. They were recognizable by their tiny rhombic (lozenge-shaped) scales. Known by several complete specimens from the Middle and Upper Devonian, the genus Cheirolepis is a primitive model for the entire group, initially described using specimens from Scotland. In North America, Cheirolepis has been found at Miguasha and in Nevada.

(24 kb) The term actinopterygian has Greek roots from pterugion (fins) and aktinos (rays). Behind this word lurk the ray-finned fish, a definition that includes all jawed actual fish except sharks, rays and chimaeras, as well as some rare sarcopterygian fish. At present, actinopterygians include more than 29,000 species, which accounts for more than 50% of all vertebrates! They are found in all aquatic habitats, from small freshwater creeks to great ocean depths, and from the smallest ponds to the greatest estuaries.

(24 kb) The term actinopterygian has Greek roots from pterugion (fins) and aktinos (rays). Behind this word lurk the ray-finned fish, a definition that includes all jawed actual fish except sharks, rays and chimaeras, as well as some rare sarcopterygian fish. At present, actinopterygians include more than 29,000 species, which accounts for more than 50% of all vertebrates! They are found in all aquatic habitats, from small freshwater creeks to great ocean depths, and from the smallest ponds to the greatest estuaries.Actinopterygians have pectoral fins made from a membrane upheld by several semi-rigid rays, called lepidotrichia, that are all attached to a single peduncle. This characteristic distinguishes them from placoderms, which have very large, limb-like basal pectoral fins, and acanthodians, equipped with immobile fins made from a single spine supporting a small membranous veil.

The fins of actinopterygians are among the most efficient in the aquatic world, not only because they allow for powerful swimming, but also (perhaps mainly) because they confer stability and manoeuvrability. The evolutionary success of this group is largely due to this morphological innovation.

The first actinopterygians go back to the end of the Silurian or the beginning of the Devonian. They were recognizable by their tiny rhombic (lozenge-shaped) scales. Known by several complete specimens from the Middle and Upper Devonian, the genus Cheirolepis is a primitive model for the entire group, initially described using specimens from Scotland. In North America, Cheirolepis has been found at Miguasha and in Nevada.

Site map | Feedback | Links | Sources | Credits

Actinopterygians

<< Diplacanthus | Cheirolepis >>