Cheirolepis

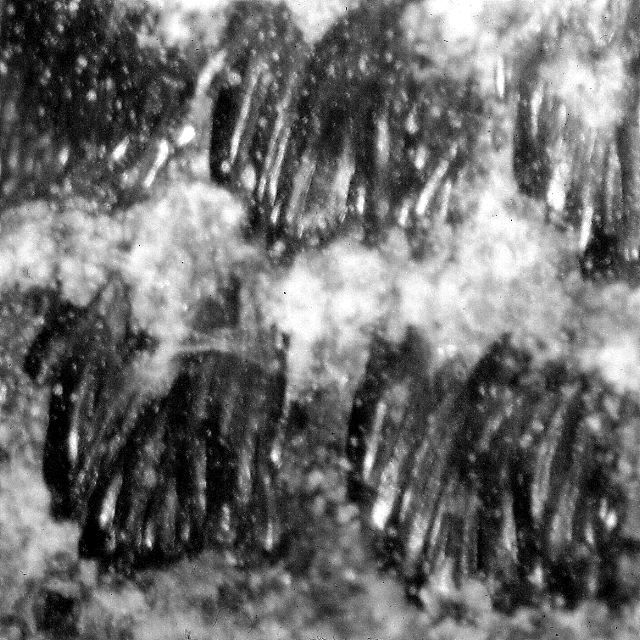

Under a magnifying glass, the lozenge-shaped scales of Cheirolepis canadensis resemble tiny hands with their four or five little crests.

(24 kb) Quite small for an actinopterygian, they are somewhat similar to acanthodian scales, reflecting the primitive nature of the species. It was the Canadian paleontologist Joseph Frederick Whiteaves who, in 1881, gave the animal its name based on its resemblance to Cheirolepis trailli from Scotland.

(24 kb) Quite small for an actinopterygian, they are somewhat similar to acanthodian scales, reflecting the primitive nature of the species. It was the Canadian paleontologist Joseph Frederick Whiteaves who, in 1881, gave the animal its name based on its resemblance to Cheirolepis trailli from Scotland.

Cheirolepis is the only representative of the actinopterygian group in the sedimentary rocks of the Miguasha cliff, and specimens are not often discovered. Its rarity is ironic given that descendants of Cheirolepis would become the dominant vertebrates during the following tens of millions of years.

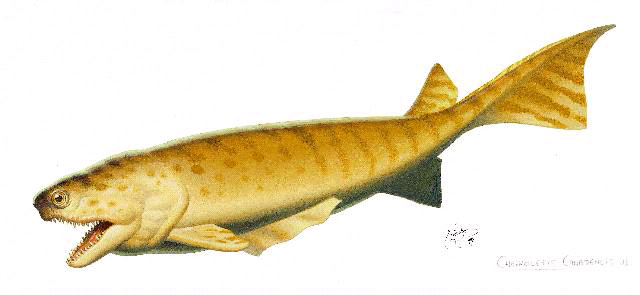

(72 kb)Growing up to 50 cm long, Cheirolepis possessed a set of physical characteristics that ensured the success of actinopterygians. It had ray fins, of course, from which the group derives its name and supremacy. But Cheirolepis also had large orbits, suggesting good sight, and a jaw with a large gape and very sharp teeth, evidence that it was an efficient predator in the Miguasha estuary. The strong and streamlined body was also designed for swift and sustained swimming.

(72 kb)Growing up to 50 cm long, Cheirolepis possessed a set of physical characteristics that ensured the success of actinopterygians. It had ray fins, of course, from which the group derives its name and supremacy. But Cheirolepis also had large orbits, suggesting good sight, and a jaw with a large gape and very sharp teeth, evidence that it was an efficient predator in the Miguasha estuary. The strong and streamlined body was also designed for swift and sustained swimming.

The fact that they were predators did not prevent the smallest Cheirolepis individuals from also being prey. Cheirolepis scales have been identified in coprolites (fossilized excrement) and cannibalism was also practiced among the species, as revealed by a small Cheirolepis inside the abdomen of a larger fellow fish.

(104 kb)It was the study of its skull bones that revealed the extent to which it could open its mouth. So large was its gape that it could swallow prey up to two thirds of its total length. Agnathans, acanthodians, and even young sarcopterygians and placoderms could all be part of its diet.

(104 kb)It was the study of its skull bones that revealed the extent to which it could open its mouth. So large was its gape that it could swallow prey up to two thirds of its total length. Agnathans, acanthodians, and even young sarcopterygians and placoderms could all be part of its diet.

Most modern actinopterygians have a homocercal tail, meaning that the upper and lower lobes are fairly equal and symmetrical, like the tail of a salmon for example. In contrast, the tail of Cheirolepis was epicercal, which means that the axis of its body continued into the longer upper lobe. Except for a few groups like the sturgeons, this primitive feature is no longer seen in actinopterygians.

The Escuminac Formation has provided paleontologists with small juvenile specimens for many species, but such is not the case for Cheirolepis. The smallest specimens thus far are a rather large 15 to 25 cm long. Perhaps their young lived in an entirely different environment. Perhaps Cheirolepis was anadromous, like today’s salmon, which means that the smaller ones lived farther upstream in fresh river water before migrating towards the sea.

(24 kb) Quite small for an actinopterygian, they are somewhat similar to acanthodian scales, reflecting the primitive nature of the species. It was the Canadian paleontologist Joseph Frederick Whiteaves who, in 1881, gave the animal its name based on its resemblance to Cheirolepis trailli from Scotland.

(24 kb) Quite small for an actinopterygian, they are somewhat similar to acanthodian scales, reflecting the primitive nature of the species. It was the Canadian paleontologist Joseph Frederick Whiteaves who, in 1881, gave the animal its name based on its resemblance to Cheirolepis trailli from Scotland.Cheirolepis is the only representative of the actinopterygian group in the sedimentary rocks of the Miguasha cliff, and specimens are not often discovered. Its rarity is ironic given that descendants of Cheirolepis would become the dominant vertebrates during the following tens of millions of years.

(72 kb)Growing up to 50 cm long, Cheirolepis possessed a set of physical characteristics that ensured the success of actinopterygians. It had ray fins, of course, from which the group derives its name and supremacy. But Cheirolepis also had large orbits, suggesting good sight, and a jaw with a large gape and very sharp teeth, evidence that it was an efficient predator in the Miguasha estuary. The strong and streamlined body was also designed for swift and sustained swimming.

(72 kb)Growing up to 50 cm long, Cheirolepis possessed a set of physical characteristics that ensured the success of actinopterygians. It had ray fins, of course, from which the group derives its name and supremacy. But Cheirolepis also had large orbits, suggesting good sight, and a jaw with a large gape and very sharp teeth, evidence that it was an efficient predator in the Miguasha estuary. The strong and streamlined body was also designed for swift and sustained swimming.The fact that they were predators did not prevent the smallest Cheirolepis individuals from also being prey. Cheirolepis scales have been identified in coprolites (fossilized excrement) and cannibalism was also practiced among the species, as revealed by a small Cheirolepis inside the abdomen of a larger fellow fish.

(104 kb)It was the study of its skull bones that revealed the extent to which it could open its mouth. So large was its gape that it could swallow prey up to two thirds of its total length. Agnathans, acanthodians, and even young sarcopterygians and placoderms could all be part of its diet.

(104 kb)It was the study of its skull bones that revealed the extent to which it could open its mouth. So large was its gape that it could swallow prey up to two thirds of its total length. Agnathans, acanthodians, and even young sarcopterygians and placoderms could all be part of its diet. Most modern actinopterygians have a homocercal tail, meaning that the upper and lower lobes are fairly equal and symmetrical, like the tail of a salmon for example. In contrast, the tail of Cheirolepis was epicercal, which means that the axis of its body continued into the longer upper lobe. Except for a few groups like the sturgeons, this primitive feature is no longer seen in actinopterygians.

The Escuminac Formation has provided paleontologists with small juvenile specimens for many species, but such is not the case for Cheirolepis. The smallest specimens thus far are a rather large 15 to 25 cm long. Perhaps their young lived in an entirely different environment. Perhaps Cheirolepis was anadromous, like today’s salmon, which means that the smaller ones lived farther upstream in fresh river water before migrating towards the sea.

Site map | Feedback | Links | Sources | Credits

Cheirolepis

<< Actinopterygians | Sarcopterygians >>

Title: Reconstruction of Cheirolepis canadensis

Author: Illustration by François Miville-Deschênes

Sources: Parc national de Miguasha

Year: 2000

Description:

Reconstruction of Miguasha’s actinopterygian fish Cheirolepis canadensis.