Miguashaia

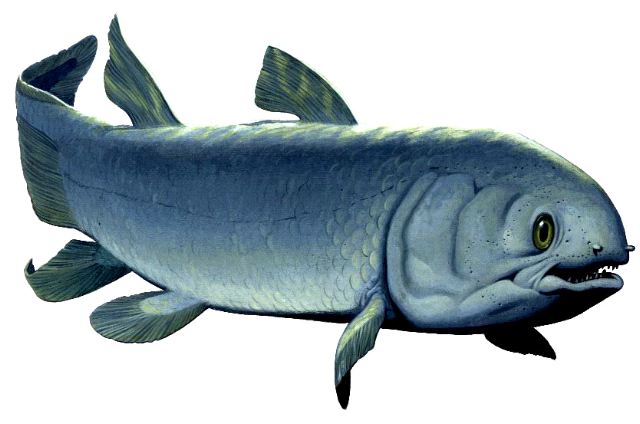

Miguashaia bureaui is the most primitive of all the actinistian fishes.

(36 kb) Instead of having three lobes, its tail was epicercal. And in the adult, the anal fin had almost no fleshy lobe, whereas the second dorsal fin had none at all.

(36 kb) Instead of having three lobes, its tail was epicercal. And in the adult, the anal fin had almost no fleshy lobe, whereas the second dorsal fin had none at all.

The name Miguashaia bureaui has a double local significance. The name of the genus highlights its geographic origins, whereas the name of the species pays homage to René Bureau, the man who played a very important role in the human history of the Miguasha site and who discovered the specimen that led to the first description of Miguashaia. Another species, Miguashaia grossi, was described in 2000 and lived in what is now Latvia during Middle Devonian time.

(80 kb)Miguashaia is the oldest actinistian with well-documented anatomy. Fossils at various stages of growth, from 7.7 to 45 cm long, have allowed paleontologists to conduct in-depth studies on its development with respect to changes in its size, proportions, and the ornamentation of its scales. The first discovered specimen was a juvenile, which caused some problems in identifying the adult specimens found later.

(80 kb)Miguashaia is the oldest actinistian with well-documented anatomy. Fossils at various stages of growth, from 7.7 to 45 cm long, have allowed paleontologists to conduct in-depth studies on its development with respect to changes in its size, proportions, and the ornamentation of its scales. The first discovered specimen was a juvenile, which caused some problems in identifying the adult specimens found later.

The present-day coelacanth, Latimeria chalumnae, has a very monotonous diet. In complete darkness, it hovers vertically with its head down deep in the Indian Ocean, skimming the bottom in search of prey. Thanks to a rostral organ at the tip of its muzzle, it can detect natural electric fields generated by small animals like crustaceans and other invertebrates. Once a potential meal is located, the coelacanth drops downwards and swallows it. The central tail lobe is what allows the fish to perform this delicate manoeuvre, known as headstand feeding.

The central tail lobe had not yet developed in Miguashaia, which means it was quite unlikely it fed by this method. The rostral organ, however, was present, and we thus assume that Miguashaia detected its prey using the same principle as Latimeria, but from a horizontal position, somewhat like small bottom-feeding sharks do today.

(36 kb) Instead of having three lobes, its tail was epicercal. And in the adult, the anal fin had almost no fleshy lobe, whereas the second dorsal fin had none at all.

(36 kb) Instead of having three lobes, its tail was epicercal. And in the adult, the anal fin had almost no fleshy lobe, whereas the second dorsal fin had none at all.The name Miguashaia bureaui has a double local significance. The name of the genus highlights its geographic origins, whereas the name of the species pays homage to René Bureau, the man who played a very important role in the human history of the Miguasha site and who discovered the specimen that led to the first description of Miguashaia. Another species, Miguashaia grossi, was described in 2000 and lived in what is now Latvia during Middle Devonian time.

(80 kb)Miguashaia is the oldest actinistian with well-documented anatomy. Fossils at various stages of growth, from 7.7 to 45 cm long, have allowed paleontologists to conduct in-depth studies on its development with respect to changes in its size, proportions, and the ornamentation of its scales. The first discovered specimen was a juvenile, which caused some problems in identifying the adult specimens found later.

(80 kb)Miguashaia is the oldest actinistian with well-documented anatomy. Fossils at various stages of growth, from 7.7 to 45 cm long, have allowed paleontologists to conduct in-depth studies on its development with respect to changes in its size, proportions, and the ornamentation of its scales. The first discovered specimen was a juvenile, which caused some problems in identifying the adult specimens found later. The present-day coelacanth, Latimeria chalumnae, has a very monotonous diet. In complete darkness, it hovers vertically with its head down deep in the Indian Ocean, skimming the bottom in search of prey. Thanks to a rostral organ at the tip of its muzzle, it can detect natural electric fields generated by small animals like crustaceans and other invertebrates. Once a potential meal is located, the coelacanth drops downwards and swallows it. The central tail lobe is what allows the fish to perform this delicate manoeuvre, known as headstand feeding.

The central tail lobe had not yet developed in Miguashaia, which means it was quite unlikely it fed by this method. The rostral organ, however, was present, and we thus assume that Miguashaia detected its prey using the same principle as Latimeria, but from a horizontal position, somewhat like small bottom-feeding sharks do today.

Site map | Feedback | Links | Sources | Credits

Miguashaia

<< Actinistians | Porolepiforms >>