Bothriolepis

(36 kb) Occurring by the thousands in the famous cliff, this “tortoise-like fossil” is easily recognized by specialists and amateurs alike, young or old. It was also the first fossil vertebrate mentioned by Abraham Gesner when he announced the discovery of the Miguasha site in his 1843 report. Not surprisingly, he confused this species with a tortoise...

(36 kb) Occurring by the thousands in the famous cliff, this “tortoise-like fossil” is easily recognized by specialists and amateurs alike, young or old. It was also the first fossil vertebrate mentioned by Abraham Gesner when he announced the discovery of the Miguasha site in his 1843 report. Not surprisingly, he confused this species with a tortoise...About a hundred different fossil species of Bothriolepis have been found around the world, but B. canadensis at Miguasha is the best known due to the large number of specimens and their excellent preservation. In fact, Miguasha’s species serves as something of a model for all Bothriolepis.

(104 kb)Bothriolepis fossils generally consist of the robust plates that surround its head and thorax, as well as the unusual streamlined fins attached to the back of its skull. This heavily boned front part of the animal is typically all that is preserved.

(104 kb)Bothriolepis fossils generally consist of the robust plates that surround its head and thorax, as well as the unusual streamlined fins attached to the back of its skull. This heavily boned front part of the animal is typically all that is preserved.Most of these bony “carapaces” have been somewhat crushed by the weight of the sediments in which they were buried. The discovey of some undeformed, three-dimensionally preserved specimens led to a review of this fish’s morphology. It appears that Bothriolepis had a much more rounded shape than previously thought, and as a direct consequence of the latest reconstructions, it is now believed that its eyes faced forward instead of upward. Of all the Bothrolepis species, only B. canadensis has been found with the unmineralized hind region preserved.

(76 kb)Some fossilized individuals almost seem to be swimming in the rock, as if groups of them were taken by surprise – buried alive by a sudden surge of sediments following some small-scale catastrophic event. This rapid burial, combined with certain physiochemical conditions that promote preservation, resulted in a number of exceptional specimens that reveal many details of their internal anatomy. The sheer abundance of specimens also allows paleontologists to document all the growth stages, from juvenile individuals less than 2 cm long, to larger, older individuals in which the bony “carapace” covering the head and thorax alone reached 23 cm in length.

(76 kb)Some fossilized individuals almost seem to be swimming in the rock, as if groups of them were taken by surprise – buried alive by a sudden surge of sediments following some small-scale catastrophic event. This rapid burial, combined with certain physiochemical conditions that promote preservation, resulted in a number of exceptional specimens that reveal many details of their internal anatomy. The sheer abundance of specimens also allows paleontologists to document all the growth stages, from juvenile individuals less than 2 cm long, to larger, older individuals in which the bony “carapace” covering the head and thorax alone reached 23 cm in length.At the beginning of the 20th century, American paleontologist William Patten discovered a bed that was very rich in Bothriolepis specimens, most of them facing in the same direction. It is an excellent example of a snapshot in time: a fish population caught momentarily fighting a fatal current. In the early 1940’s, cross-sections of many of these specimens revealed the traces of internal organs preserved as casts. In some cases, the organs were forcefully filled with the same sediment that engulfed the animal. In others, the organs were filled with sediment ingested by the fish while feeding on the muddy bottom.

(40 kb)The excellent condition of the Patten specimens made it possible for paleontologists to trace the position of the animal’s main internal cavities, from the pharyngeal cavity in the head to the intestinal system backward. It turns out that the internal structures are strongly suggestive of a spiral valve intestine, very similar to that of sharks today.

(40 kb)The excellent condition of the Patten specimens made it possible for paleontologists to trace the position of the animal’s main internal cavities, from the pharyngeal cavity in the head to the intestinal system backward. It turns out that the internal structures are strongly suggestive of a spiral valve intestine, very similar to that of sharks today.The slicing work also inspired a stunning hypothesis, which proposed that Bothriolepis was equipped with lungs. This idea is based on the presence of two internal sacs that appear to be connected to the pharyngeal cavity. Highly controversial, the presence of these sacs, or presumed “lungs”, has recently been confirmed in a three-dimensional specimen that was opened lengthwise. We also know that the walls of these mysterious organs were fed by a network of blood vessels that converged toward the centre of the animal: the place where its heart would have been. The delicate traces of these blood vessels can be seen directly on the ventral surface of the thorax interior in two specimens. It may be that following the death of the animal, the iron in its hemoglobin oxidized, staining the adjacent sediments.

(128 kb)How many Bothriolepis species are there at Miguasha? It seems fairly certain that there are at least two, with the second species discovered and described in 1924. Named B. Traquairi, after Scottish paleontologist Ramsey Heatly Traquair, the one and only specimen officially assigned to this species has a more slender body than B. canadensis. A population of Bothriolepis, whose long shapes are reminiscent of B. Traquairi, was discovered in a bed of red sandstone in the Escuminac Formation. Although the contents of this layer have not yet been described, the discovery appears to confirm the presence of at least two species of Bothriolepis at Miguasha.

(128 kb)How many Bothriolepis species are there at Miguasha? It seems fairly certain that there are at least two, with the second species discovered and described in 1924. Named B. Traquairi, after Scottish paleontologist Ramsey Heatly Traquair, the one and only specimen officially assigned to this species has a more slender body than B. canadensis. A population of Bothriolepis, whose long shapes are reminiscent of B. Traquairi, was discovered in a bed of red sandstone in the Escuminac Formation. Although the contents of this layer have not yet been described, the discovery appears to confirm the presence of at least two species of Bothriolepis at Miguasha.Site map | Feedback | Links | Sources | Credits

Bothriolepis

<< Antiarchs | Arthrodires >>

Title: Reconstruction of Bothriolepis canadensis

Author: Illustration by François Miville-Deschênes

Sources: Parc national de Miguasha

Year: 2003

Description:

In 1842, Bothriolepis was the first fish discovered at Miguasha. Although originally mistaken for a tortoise, paleontologists realized it was a primitive fish known as a placoderm, which belongs to the antiarch group. Its head, thorax and even its anterior fins were covered by bony plates. Reconstruction by François Miville-Deschêsnes.

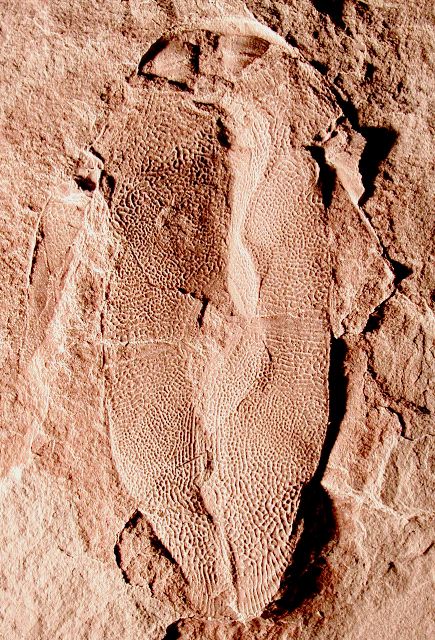

Title: Complete specimen of Bothriolepis canadensis

Author: Parc national de Miguasha

Sources: Parc national de Miguasha

Year: 2006

Description:

An example of a complete specimen of Bothriolepis canadensis showing the unmineralized rear part of the body. It is a rare find because the lack of mineralization makes it difficult to preserve this part of the animal.

Title: Four Bothriolepis specimens

Author: Parc national de Miguasha

Sources: Parc national de Miguasha

Year: 1997

Description:

Part of a rock layer containing four Bothriolepis canadensis individuals. The sample, which is kept at the American Museum of Natural History in New York City, was collected by William Patten in the early 1900’s.

Title: Growth stages of Bothriolepis canadensis

Author: Richard Cloutier

Sources: Parc national de Miguasha

Year: 1997

Description:

Bothriolepis canadensis is an abundant species in the Escuminac Formation, from immature individuals to large adult specimens.

Title: A Bothriolepis specimen with an elongated body

Author: Parc national de Miguasha

Sources: Parc national de Miguasha

Year: 2007

Description:

A species of elongated Bothriolepis is found in a red sandstone bed of the Escuminac Formation. The specimens from this bed are similar to those of B. traquairi, described in 1924.